Read the full story and hear clips at Rolling Stone.

Imagine hurtling yourself back in time to the original Woodstock festival in 1969, finding a good, relatively dry spot to chill, and settling in to hear more than three straight days of music. No, not possible, but the closest anyone may come to that experience will arrive this August. Pegged to the 50th anniversary of the event, Woodstock 50 — Back to the Garden — The Definitive 50th Anniversary Archive, a 38-disc box set, will include every note of music played at the festival (save for three songs), some of it released for the first time ever.

Previous Woodstock collections, starting with the original 1970 triple LP and continuing through a 2009 multi-disc box, cherry-picked select songs (or didn’t include certain acts altogether). By comparison, Woodstock 50, to be released by Rhino, has it all: every act and 432 songs, 267 of which have never been officially released before, for a total of nearly 36 hours of recordings, along with crowd announcements (“Somebody somewhere is giving out some flat blue acid,” “Please meet Harold at the stand with the blood pills”) and other sonic memorabilia from the festival.

Complete performances of the Who, Joe Cocker, Sly and the Family Stone, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and others, along with acts who weren’t in the movie or the original Woodstock album, like the Band, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival and Janis Joplin will be available for the first time. The tracks are also arranged chronologically, by day and set times, from Richie Havens’ opening set that August Friday in 1969 to Jimi Hendrix’s festival-closing set on Monday morning. To ease the overwhelming listening experience, each act is accorded its own disc.

“There have been large boxed sets devoted to particular eras or tours — the Grateful Dead do a great job of that sort of thing — but there’s never, to my knowledge, been an attempt to present a large-scale durational experience of this sort,” says Andy Zax, the Los Angeles producer and archivist who co-produced the set with Steve Woolard. “The Woodstock tapes give us a singular opportunity for a kind of sonic time travel, and my intention is to transport people back to 1969. There aren’t many other concerts you could make this argument about.”

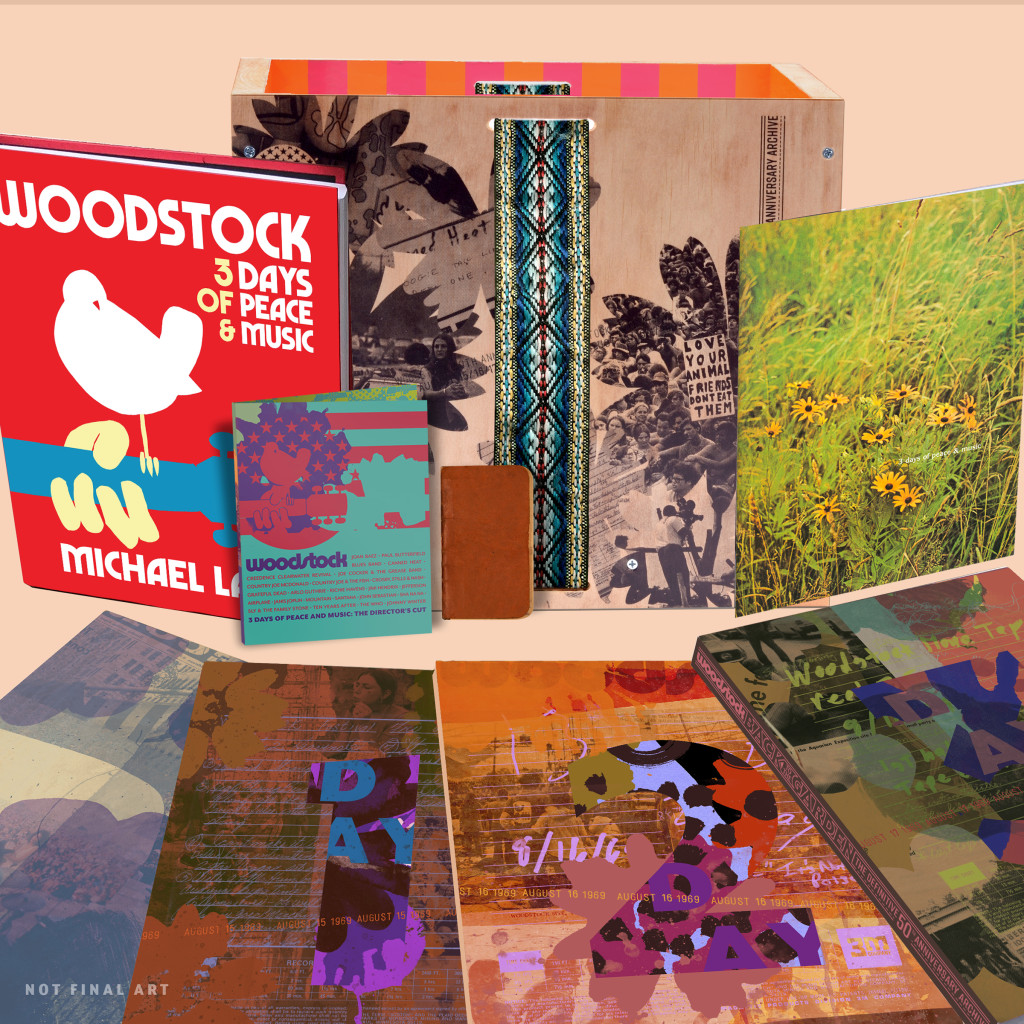

The box — which will also include a Blu-ray of Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock movie, a guitar strap and a replica of the original program, among other items — will cost $799. More condensed versions — a 10-disc set and a 3-disc one — will also be available. In the mega-box, the 38th disc includes various audio flotsam. The “Groesbeek Reel,” named after festival sound recordist Charles Groesbeek, includes comments from random attendees taped by Grosbeak–like, Zax laughs, “this one guy moaning about what a disappointing experience it was and that it was a sell-out. It’s a great slice of real people in the moment reacting to it, which pleases me immensely.”

In late 2005, Zax visited a Warner Brothers storage space in Los Angeles, where a pile of tapes from the Atlantic Records vault in New York had been shipped. There, he found dozens of boxes of one-inch eight-track recordings from Woodstock. “From the moment I saw those tapes, I was like, ‘Oh my God, there’s so much more than I’d ever thought,’” he says. “It was clear to me that no one was exploring this stuff and dealing with it in totality. Here was this vast trove of material not treated correctly.”

Zax said he initially considered a complete festival box but didn’t have “institutional support” back then and opted for the 40th anniversary 2009 box, which at least contained more unheard songs than ever before. But Zax and Woolard still had their work cut out for them. They had to deal with what Zax calls the “Woodstock first-song curse.” “There are tons of instances where they would forget to turn on a vocal mic,” he says, “so the song starts and someone’s voice isn’t audible until 45 seconds in, or the drums disappear.” To compensate, Zax used alternate tapes from the soundboard to fill in certain gaps.

Zax also found that the reel of Sly Stone’s performance was cut up and spliced into “100 small pieces,” he says. “It was like old-school film editing — bits of tape hanging like a million No-Pest Strips.” The original tapes of Havens’ set, which were handed over to the late folksinger about 20 years after the festival, mysteriously vanished, so Zax and his team had to opt for a superior copy instead of the original tape.

For Zax, the experience of hearing the unreleased music was often revelatory. “There was always this perception that Joplin’s set was poor and didn’t represent her at her best,” he says. “It may not have been the greatest night of her life, but listening to it on tape, it really sounds powerful.” The same, he says, goes for the Dead. The band has famously denigrated its Woodstock performance, in part due to electrical problems onstage, but Zax says, “They were a formidable performing unit in 1969, so it’s not an embarrassment.” And Zax calls Creedence’s never-heard full set “one of the best performances at Woodstock — top 3 or top 5, for sure. The fact that it wasn’t out in its entirety until now is flabbergasting.”

In general, Zax admits that some of the acts had less than pleasant recall of playing the festival, which colored their memories of the performances and made some hesitate about signing off. “There was some skepticism, like, ‘You want to issue the whole performance? Are you insane?’” he says. “There’s not one person at Woodstock who was entirely happy with what they did. Ambivalence is about the best you tend to hear from people. And others are like, ‘That was a horror show — every minute was torture.’ But it’s a big part of people’s legacy, and 50 years is the kind of number that makes people think of one’s legacy.” (As for the missing numbers: the Hendrix estate asked that two of his songs not be included, for aesthetic reasons, and one of Sha Na Na’s performances is missing due to a tape gap.)

But according to the producer, one pragmatic argument helped convince the artists or their estates to give the go-ahead for their tracks on Woodstock 50. This January, any unreleased performances or recordings from 1969 will go into the public domain — and will thereby be legal and exploitable in Europe. “Not bootleg, but legit,” he says. “So there’s a pragmatic reason for protecting your copyright on a performance.”

Looking back over the 14-year journey to the most comprehensive Woodstock set, Zax feels the arduous work was worth it. “The movie is one version of Woodstock,” he says. “This is an audio verite documentary about the Sixties.”