The Summer of Love To Come – Interview with Grace

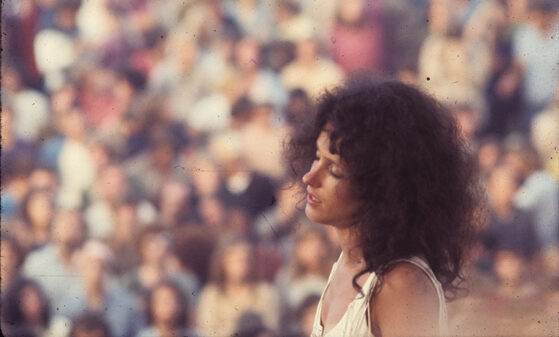

Today, like in 1967, an intense unity has developed in the wake of dissatisfaction. We speak to Grace Slick about the possibilities of a Summer of Love to come.

Read the whole article on HAPPY MAG.

Restrictions on socialising are forcing the young and old to re-evaluate their relationships and priorities. Rising unemployment and a subsequent lack of financial security has led to rampant and commonplace anxieties. Many industries are surviving only on the call of government support. Non-essential workers stew away at home while their essential counterparts man the frontline. Retail is shuttered and whole business districts lie dormant. Limits on travel are encouraging Australians to turn inward for their aspirations, arts, and culture.

When Australia emerges from this most peculiar of times, the population will be bound by a residual anxiety and a simultaneous eagerness to participate in public life. More than ever before, we’ll be joined by common experience and the mutual desire to find stability and purpose in our local worlds. While the circumstances couldn’t be more different, it seems that what we have before us are the makings of a new Summer of Love, one that might not be defined by public gatherings like Monterey and Woodstock, but by a shared consciousness and desire for connection nonetheless.

50 years ago, the soundtrack to the Summer of Love was acid rock, a sound pulsating with the two mainstays of the hippie lifestyle: drugs and music. The psychedelic experience and the hopeful, ascendant music that scored it rang the movement’s catch-cry home, “Make Love, Not War.” At the heart of this new sound was a band called Jefferson Airplane, fronted by a woman who oozed the hippie lifestyle, Grace Slick.

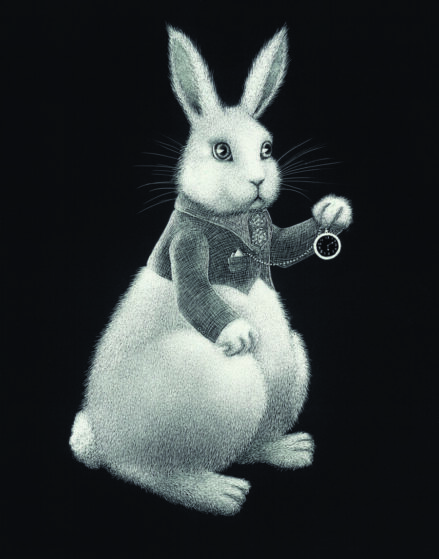

Grace Slick and the Jefferson Airplane rose in popularity with tracks like Somebody to Love and White Rabbit, the latter a song that ties the adventures of Alice in Wonderland to the mind-altering experiences of the 1960s. Harbouring away from COVID-19 in her home in Los Angeles, Slick finds the parallels between the ’60s and now worth the conversation, particularly with regards to togetherness, arts localisation, change, and hope.

Despite being bound by a common fear of the virus, Slick comments that the globe has never been more “self-interested” and divided. During the 1967 Summer of Love, “you were either a hippie, or you were straight.” The simplicity of this political divide saw people mobilise effectively against a common cause. Today, however, Slick talks of “too many cooks ruining the soup,” and a proliferation of small interest groups “making it hard to get stuff done.” There’s “a greater consciousness of a spread between people” despite the media saying “in big block letters we’re all in this together,” and the fear of COVID-19 experienced on an individual level is reducing any collective mentality from developing.

Unlike her stance on unity in this period, Slick sees clear commonalities in the way local arts will be embraced in a travel-restricted world. Slick contests the romanticised image of Woodstock as the iconic festival of the 1960s, saying that “it was just big, and unfortunately in America, big means marvellous.” While it was “interesting playing for half a million people,” the grassroots Monterey Pop festival is the event Slick truly celebrates. “It was smaller and the artists actually got to see each other play… I’d heard Jimi Hendrix, but I’d never seen him. I’d heard The Who on record, but I’d never seen them.” Slick suggests that reduced international mobility in the new world will see a surge in support for local arts and sees no reason why the community culture of 1967 won’t be reignited.

While the 1967 Summer of Love arrived on the back of generational change, in 2020, Slick expects COVID-19 to precipitate one. Slick comments that “in the ’50s, you didn’t have sex before you were married. You didn’t swear like I always had – my mother used to say, Grace, you sound like a truck driver!” By the 1960s, “it was completely different,” and Grace indulged in every pleasure on and off the menu.

“Drugs are like cheeseburgers – you might not have them three or four meals a day, but you still love them all the same.” Slick expects a range of societal changes to follow COVID-19, from a reluctance to participate in large public events to a broadened fashion catalogue of “designer hazmat suits, designer masks, and designer gas masks.”

The greatest divergence Slick detects between the Summer of Love that was and the one to come is the population’s understanding of how to affect social change. Slick muses that the hippies were bound by their hope for “a change in attitude about the war,” but hope alone was their vehicle for change and they failed to invest meaningfully in diplomacy and politics. Slick comments that today, it’s understood that positive change is a consequence of working together with the government and its agencies.

“You can’t just have the California and New York governors being smart, it has to be the federal government and at the moment we don’t have one.”

Strip back the fetishised image of the Summer of Love as a cultural renaissance and what you have is a more commonplace experience of collective rebellion. With restrictions on socialising, rising unemployment, home lives fraught with new pressures and a future that looks most uncertain, what we are experiencing is a convergence of our world’s concerns.

While acid rock and the war in Vietnam might no longer be on our radar, it seems that on the local and national level, we’re all back to campaigning for a more compassionate future.